A brainy panel tackle your questions

Interview with

How are memories formed and lost? Is Alzheimer's just an extreme version of normal aging? And to what extent does genetics play a role? Can we protect ourselves from developing the disease? We get our head around your questions...

How are memories formed and lost? Is Alzheimer's just an extreme version of normal aging? And to what extent does genetics play a role? Can we protect ourselves from developing the disease? We get our head around your questions...

We've accrued a brainy panel of experts, bringing together a geneticist, a psychologist, and an epidemiologist - so, someone who studies genes and behaviours in society.

Starting with Pekka Olinka, she got in touch asking, "How does memory work in the first place and how does it go wrong in Alzheimer's?"

John - Okay, my name is John Gallacher. I'm an epidemiologist. You could try and answer this at different levels, but just to keep you fairly straightforward, our memory works by the brain making new connections as it learns new material. These memories, these connections, are then retrieved for different purposes. Now, if those memories are wiped because the brain is mashed for dementia or for any other reason, of course, there's nothing there to retrieve. The other side of that coin is, if you are having trouble encoding or making new connections in the brain, obviously, there is less material there which has been coded or remembered in order to retrieve in the first place.

Karen - Karen Ritchie, I'm a neuropsychologist and an epidemiologist. What one needs to understand is that the learning takes place at two levels, at least, and there is a level at which we take in a certain amount of material and we analyse it and then we store it. If it is stored into a longer store and quite often, what we see with Alzheimer's disease is this inability to be able to store in the short term and to analyse, and therefore, pass it into longer term memory.

Hannah - So, just going back to these connections between brain cells and their involvement in memory, you do actually see a decrease in post mortem samples of patients with Alzheimer's in these connections?

John - Yes, in the various dementing processes, it's essentially a process of neuronal death. Therefore, the number of cell is reduced, the number of connections reduce, and therefore, the functionality of the brain reduces.

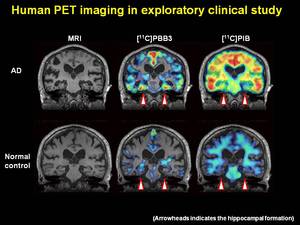

Karen - And I think we can afford to lose quite a lot of brain cells. I think one of the most important thing is not how much we lose, but exactly where we're losing them from. There are crucial parts in the brain - we talk about the hippocampus which is very much involved in learning, where cell death in those areas are going to have far more impact than in some other areas.

Kevin - I'm Kevin Morgan, University of Nottingham. I'm a human geneticist. I think what the others have referred to is the neuronal reserve hypothesis which I think is a very plausible explanation. You can think of your brain as an organ or a tissue, sort of use it or lose it. So, the more connections you can make, the more you can afford to potentially lose down the line. So, I think it's good to keep sort of exercising your brain doing puzzles, read and it certainly can't do any harm and makes life a bit more interesting as well.

Hannah - Certainly does and we'll be talking later on about things that we can do to help protect our brain against Alzheimer's. But also, It Gran has been in touch via Twitter saying, "How do you distinguish between normal old age loss of memory and Alzheimer's when diagnosing?" We all really tend to associate memory loss with getting older, but at what point does that become Alzheimer's or dementia? What's the difference? Is there a difference?

Karen - There are differences. I think firstly, that we have problems with memory at all ages. But I think as we get older, we start to become more and more sensitive about them. But I think there are some particular types of learning that we tend to lose.

We often test people using something like word lists because it tries to capture this first phase of memory where we try to take in information and organise it in order to be able to store it. Sometimes we find that this specific capacity has been lost. But the person still has intact ability to recall things that occurred quite some time ago. There's some evidence to suggest that the parts of the brain that are the first really to be hit, parts of the brain that are very much involved in visuospatial memory - that is the learning of the spatial location of things. This seems to be far more specific to Alzheimer's disease than into normal ageing.

John - You have different effects, different decrements with different sorts of dementia. So, we've talked about Alzheimer's disease particularly, but if you have vascular dementia, you'd have a different set of symptoms. Now, the difference, you could argue between a particular disease and normal ageing, maybe one just a degree. I mean, that the brain is responding to insults and challenges all the time. And over time, it's robustness to adapt will change and then maybe will be for different functions and critical moments where actually the decline drops rather rapidly and at which point, we will become symptomatic for dementia.

Kevin - I think it's important to remember that the clue is in the name Alzheimer's disease, it is a disease and I think if you go back perhaps 4 or 5 years ago, one of the big areas that was debated was the fact that if we all lived long enough, we'd all get Alzheimer's disease if it was a normal part of the ageing process. I think you just look around and see the people in their 90s or even over 100 years old that are cognitively as sharp as a button. So, it doesn't necessarily have to happen. So, there are mechanisms that kick in and as John said, there will be some individuals that are more vulnerable to those insults. But I think it's important that people realise that the normal ageing process and neurodegeneration are two distinct entities.

Karen - I think there's a whole question of what is normal. We used to think for example that cardiac capacity reduce across time with ageing. We now know that that's not the case once you take into account disease processes. Just as we've always said, it's normal to lose your memory, it's normal to have word-finding difficulties with age. I think particularly, a baby boomer era is less and less tolerant of being told that this is normal for age and is actually looking some way to rectify this.

Hannah - Thank you. Gerald McMullen has got in touch saying, "What's the role of genetics in developing Alzheimer's or dementia down the line?" Could there be a genetic test in the future that he could use to screen himself for?

Kevin - Good question. I think currently, it's a little bit premature to talk about people going for a genetic test. I think familial AD which is the rare inherited forms, they come for 2%, maybe 5% at most of Alzheimer's disease. These are the forms that the age of onset is very young, 40s and 50s - the genes are known. So, if there's a familial history, it would make sense in being screened for those particular genes.

Now, the genes involved in later onset or the sporadic form which is the remaining 95%, we're only just beginning to get a handle on what those genes are. It's debatable how big a role those genes play and we certainly haven't found them all.

So, whilst we can test for all of those genes now, it's a simple matter of doing the genotyping which is not a problem. The reality of it is, is you would be testing when you didn't have a full picture of what you wanted to test. So, you'll be covering perhaps only 20%, 25% of the known causes.

Once we've got a full understanding of all the genes involved, then these tests are likely to become a reality. It will depend on individuals deciding whether they want to know and society will dictate whether a genetic test has some meaning when currently, the treatments are running sort of decades behind the scientific findings.

Karen - I think there are also ethical issues about doing genetic screening when there isn't an efficient treatment that is behind it. We already have seen that when the first strong candidate gene apoE was discovered that for those of us who conducted community research, there was often pressure on us to reveal the apoE status to families, and perhaps even more alarming to people who were responsible for care institutions. They wanted to be able to exclude people with apoE from entering to institutions because they were very likely to develop Alzheimer's disease. So, I think there are more issues than just being able to screen genetically.

Hannah - What about the role of environmental factors? Are there particular lifestyle choices that we can make that will help protect us against developing Alzheimer's down the line?

John - I think there are. The question isn't, are there lifestyle choices we can make. It's much more, what will the impact be. All the evidence points to a fairly substantial reduction in risk for vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease by taking more exercise, having what you might call a healthy diet, fruit and vegetables, low saturated fats, and fatty fish, reducing our weight, non-excessive alcohol consumption, and non-smoking. So, these things add up together.

Karen - I think we're also limited by the fact we know very little about environmental factors. The only environmental factors we really looked at are those that occur in old age because our studies are conducted in old age. That's where the cases are. It's not necessarily where the risk exposure is, that in fact, we could be exposed to many risks much earlier in life. Perhaps even in utero that might have an impact later on and could be potentially reversible factors.

Kevin - I think the reality is, we can debate about the role of environmental factors, but the bottom line is that things that will stop you getting strokes and heart attacks, we should all really be embracing those. If there's a benefit in preventing dementia then we should all be sort of be plugging into that. I'm willing to risk the fact that these things might be doing some good as well as stopping high blood pressure and heart attacks can potentially the risk for dementia as well.

Hannah - And final question now, John Haze has been in touch saying, "What kind of treatments are available for Alzheimer's and will we even come up with a cure?"

Kevin - It's a good question. Personally speaking, my understanding of memory process and the fact that what you're doing is destroying neuronal connections that you've built up throughout your life is that finding a cure or finding treatment that can reverse that process is very daunting task indeed. I think what's more realistic is that drugs can be developed that slow the process down.

Hannah - Thanks to John Gallacher, epidemiologist from Cardiff University, Karen Ritchie, psychologist from the French National Institute of Medical Research, and Kevin Morgan, geneticist from Nottingham. This is me, Hannah Critchlow reporting from the Alzheimer's Research UK Conference for this special Naked Neuroscience episode sponsored by Alzheimer's Research UK.

Comments

Add a comment